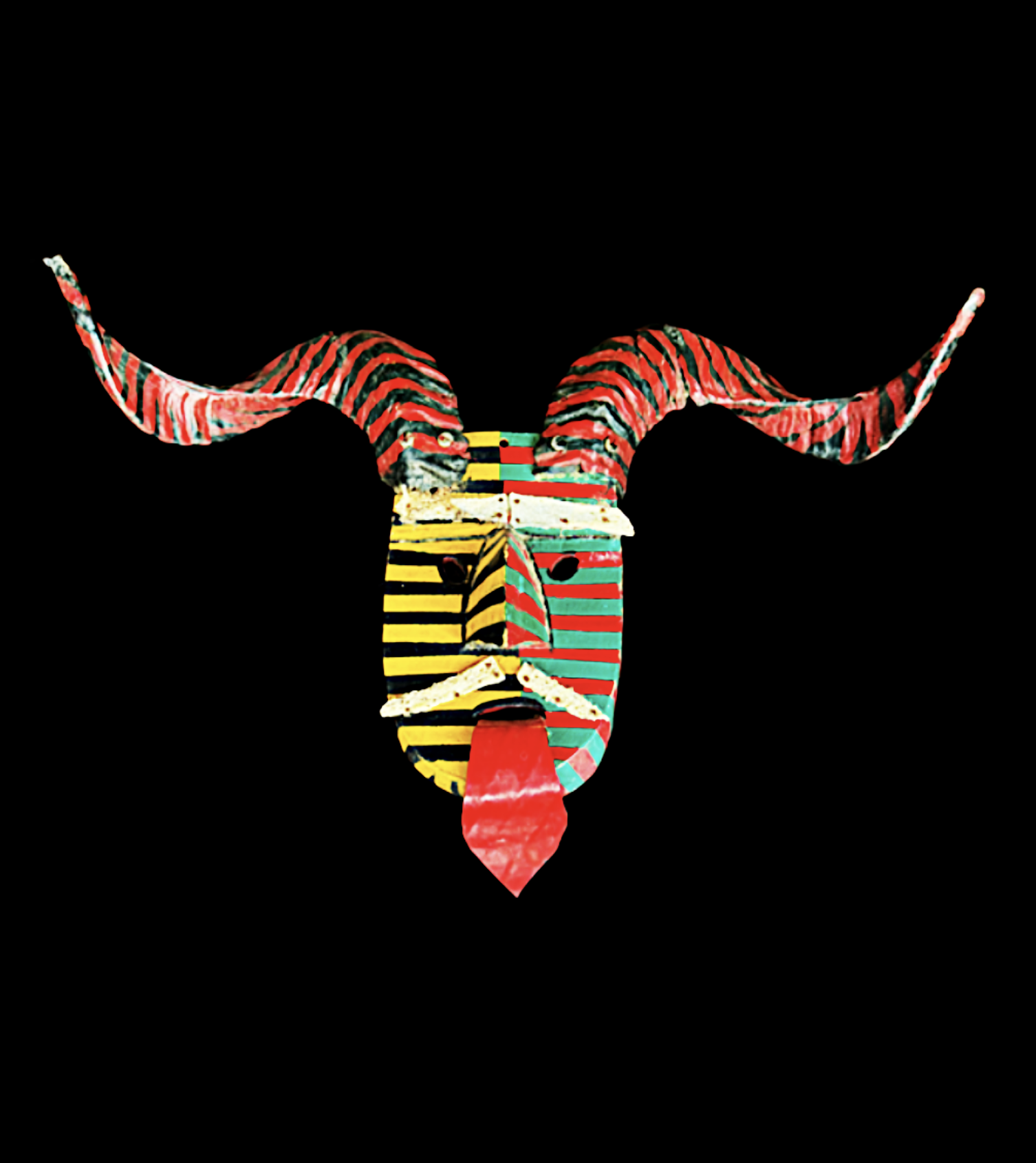

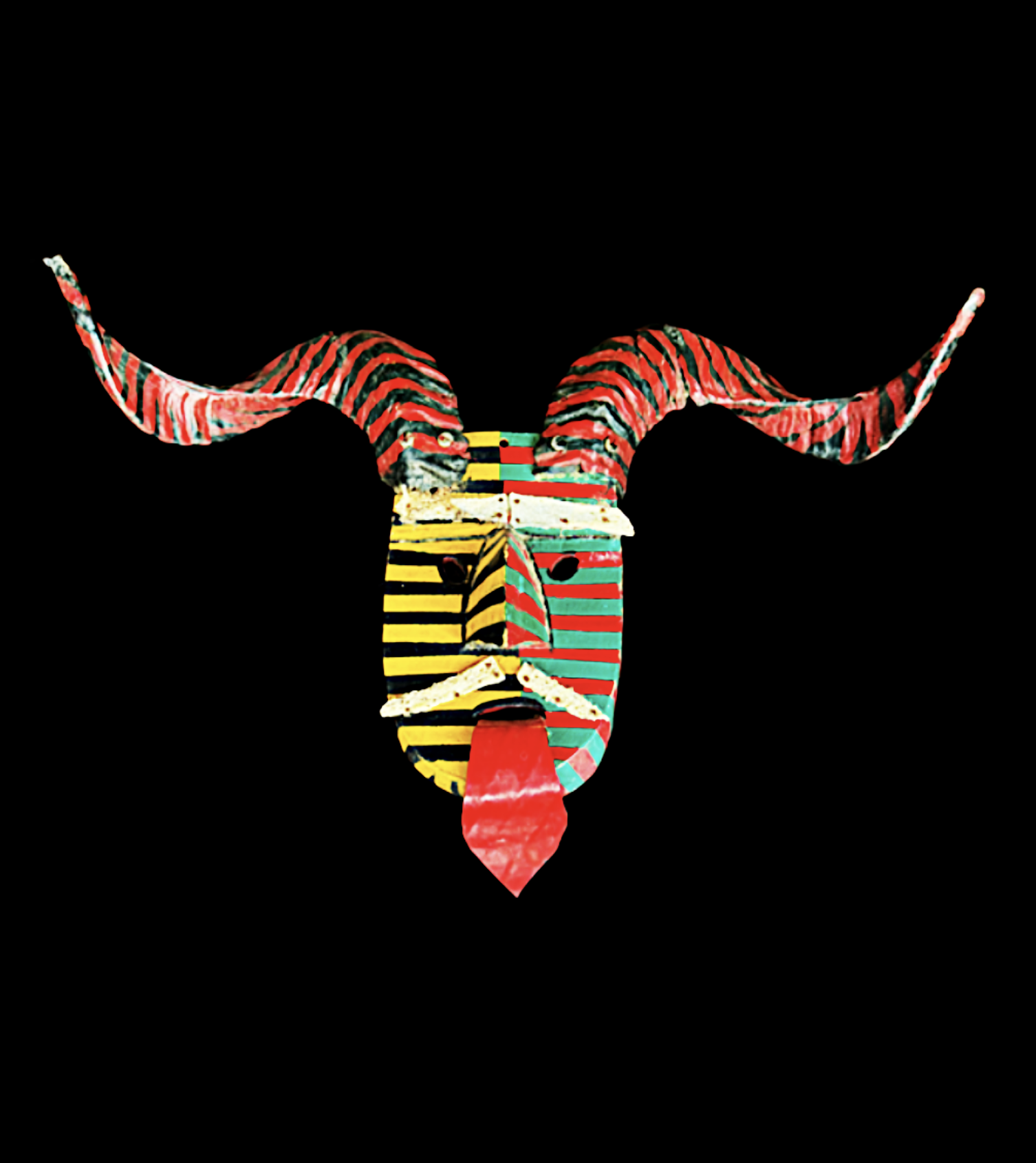

Title: Mexican Antique Goat Horn Devil Arts And Crafts Carnival Wood Painted Mask

Shipping: $29.00

Artist: N/A

Period: 20th Century

History: Art

Origin: North America > Mexico

Condition: Very Good

Item Date: N/A

Item ID: 722

Fabulous 20th-century Mexican antique Arts and Crafts carnival mask, hand-carved from wood with goat horns, a red tongue, and vibrant, original painted geometric details crafted from found objects. Approximate size 24 inches wide 14 inches tall. This remarkable antique mask, featuring goat horns and vivid painted designs, is a testament to the rich Mexican tradition of Carnival. The festival, eagerly anticipated each year, serves as a vibrant celebration where people express their religious devotion and cultural heritage through dance, religion, culture, and art. The history of religious carved mask-making in Mexico is deeply rooted in the blending of indigenous traditions and Catholic influences brought by Spanish colonization. Pre-Columbian cultures, such as the Maya and Aztecs, used masks in religious rituals to honor deities, celebrate agricultural cycles, and depict mythological stories. With the arrival of the Spanish, indigenous artisans adapted their techniques to create masks for Catholic festivals, such as the Day of the Dead and Carnival, incorporating Christian iconography alongside traditional designs. These masks, often carved from wood and painted with vibrant colors, served as tools for storytelling, performance, and cultural expression. Today, they remain a symbol of Mexico's rich spiritual and artistic heritage, celebrated in traditional dances and ceremonies across the country.

When the Spanish arrived in Mexico in the early 16th century, they brought Christianity, specifically Catholicism, as a core part of their conquest and colonization. The Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church were intertwined, aiming to convert indigenous peoples to Christianity. Evangelization Efforts: Catholic missionaries, particularly Franciscans, Dominicans, and Jesuits, played a central role in converting indigenous populations. These missionaries used mass baptisms as a way to rapidly introduce Christianity, often as part of broader efforts to assimilate indigenous peoples into European cultural and religious norms. Indigenous Beliefs: Indigenous peoples in Mexico had their own complex spiritual systems, which included polytheism, rituals, and beliefs in deities like Quetzalcoatl and Huitzilopochtli. Missionaries sought to replace these systems with Christian doctrine but also adapted some elements to facilitate conversion. Mass Baptisms: A Religious and Social Tool Mass baptisms became a practical solution for the vast number of conversions the Church sought to achieve. Symbolism of Baptism: Baptism, as the first sacrament in Christianity, marked the formal entry into the faith. For indigenous peoples, it symbolized acceptance into a new spiritual community, although its significance was often layered with existing beliefs. Scale: Missionaries often baptized thousands at once, using holy water to bless entire groups. These ceremonies were sometimes theatrical, involving processions, music, and imagery to make Christianity appealing and understandable. Syncretism: The Religious Crossover. As Catholicism spread, indigenous beliefs and practices intertwined with Christian traditions, creating a unique form of religious syncretism in Mexico. The Virgin of Guadalupe: A key example of this crossover is the Virgin of Guadalupe, a Marian apparition that became a central figure in Mexican Catholicism. She was perceived as a merging of the Catholic Virgin Mary and Tonantzin, an Aztec mother goddess. Festivals and Rituals: Indigenous ceremonies and Catholic sacraments blended, leading to vibrant festivals like Día de los Muertos, which incorporates pre-Columbian practices with Catholic prayers and rituals. Impact on Family and Community Mass baptisms reshaped family and community dynamics: Godparent System: The introduction of godparents (padrinos) in baptisms reinforced community ties, creating lifelong spiritual bonds that extended beyond biological family. Social Identity: Baptism became a marker of Christian identity and, by extension, social acceptance under colonial rule. Modern Reflections Today, the legacy of these mass baptisms is visible in Mexico’s predominantly Catholic population and the syncretic traditions that define Mexican spirituality. Despite the often coercive nature of these conversions, the resulting cultural synthesis has created a rich and unique religious identity. This history reflects a powerful narrative of resilience and adaptation, where indigenous and Christian traditions continue to coexist and evolve.